Cryptography in Information Security

From Computing and Software Wiki

(→Headline text) |

|||

| (98 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | + | [[Image:public_key_cryptography_and_pgp.jpg|thumb|Cryptography is Our Security|right|'''Cryptography is Our Security''']] | |

| - | ''' | + | ===Introduction=== |

| - | + | The word [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryptography cryptography] comes from two Greek words meaning "secret writing" and is the art and science of concealing meaning. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryptanalyst Cryptanalysis] is the breaking of codes. The basic component of cryptography is a | |

| - | + | cryptosystem. | |

| - | + | <br>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quintuple Quintuple] (E, D, M, K, C): | |

| - | + | * M set of plaintexts<br> | |

| - | + | * K set of keys<br> | |

| + | * C set of ciphertexts<br> | ||

| + | * E set of encryption functions<br> | ||

| + | * D set of decryption functions <br> | ||

| + | The goal of cryptography is to keep [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enciphered enciphered] information secret. An [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adversary adversary] wishes to break a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ciphertext ciphertext]. Standard cryptographic practice is to assume that one knows the algorithm used to encipher the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plaintext plaintext], but not the specific cryptographic key (in other words, she knows D and E). One may use three types of attacks. | ||

| - | + | =Classical Cryptosystems= | |

| - | + | Classical cryptosystems (also called single-key or [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symmetric_cryptosystems symmetric cryptosystems]) are cryptosystems that use the same key for encipherment and decipherment. So the sender, receiver share common key. Keys may be the same, or trivial to derive from one another. The are sometime called symmetric cryptography. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | The | + | ==Cæsar cipher== |

| - | + | The action of a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar Caesar] cipher is to replace each plaintext letter with one a fixed number of places down the alphabet. This example is with a shift of three, so that a B in the plaintext becomes E in the ciphertext | |

| + | [[Image:Images.jpg|thumb|Casear Cipher Machine|right|'''Caesar cipher machine''']] | ||

| + | * '''EXAMPLE''': | ||

| + | The Caesar cipher is the widely known cipher in which letters are shifted. For example, if the key is 3, the letter A becomes D, B becomes E, and so forth, ending with Z becoming C. So the word "HELLO" is enciphered as "KHOOR." Informally, this cipher is a cryptosystem with: | ||

| + | M = { all sequences of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_letters Roman letters] }<br> | ||

| + | K = { i | i an integer such that 0 ≤ I ≤ 25 }<br> | ||

| + | E = { Ek | k≤ K and for all m M, Ek(m) = (m + k) mod 26 }<br> | ||

| - | + | Representing each letter by its position in the alphabet (with A in position 0), | |

| - | + | "HELLO" is 7 4 11 11 14;<br> | |

| - | + | if k = 3, the ciphertext is 10 7 14 14 17, or "KHOOR." | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | D = { Dk | k K and for all c C, Dk(c) = (26 + c – k) mod 26 } | |

| - | + | Each Dk simply inverts the corresponding Ek. | |

| - | + | C = M | |

| - | + | because E is clearly a set of onto functions. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | ==Vigènere cipher== | ||

| + | A longer key might obscure the statistics. The Vigenère cipher chooses a sequence of keys, represented by a string. The key letters are applied to successive plaintext characters, and when the end of the key is reached, the key starts over. The length of the key is called the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Period_of_the_cipher period of the cipher]. Because this requires several different key letters, this type of cipher is called [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyalphabetic polyalphabetic]. | ||

| + | [[Image:Vigenere.png|thumb|Vigenere Square Table|180px|right|''' Vigenere square ''']] | ||

| - | + | *'''EXAMPLE''': The first line of a limerick is enciphered using the key "BENCH," as follows:<br> | |

| - | + | Key B ENCHBENC HBENC HBENCH BENCHBENCH<br> | |

| - | + | Plaintext A LIMERICK PACKS LAUGHS ANATOMICAL<br> | |

| + | Ciphertext B PVOLSMPM WBGXU SBYTJZ BRNVVNMPCS<br> | ||

| - | + | For many years, the [http://www.cas.mcmaster.ca/wiki/index.php/Conventional_Encryption_Algorithms Vigenère] cipher was considered unbreakable. Then a Prussian cavalry officer named [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasiski Kasiski] noticed that repetitions occur when characters of the key appear over the same characters in the | |

| - | + | ciphertext. The number of characters between the repetitions is a multiple of the period. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ''One Time Pad'' | |

| - | The | + | The one-time pad is a variant of the Vigenère cipher. The technique is the same. The key string is chosen |

| + | at random, and is at least as long as the message, so it does not repeat. | ||

| - | + | ==Data Encryption Standard== | |

| - | The | + | The Data Encryption Standard (DES) was designed to encipher sensitive but nonclassified data. |

| - | + | It is [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bit-oriented bit-oriented], unlike the other ciphers we have seen. It uses both [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transposition_cipher transposition] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Substitution_cipher substitution] | |

| - | + | and for that reason is sometimes referred to as a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Product_cipher product cipher]. Its input, output, and key are each 64 bits long. | |

| - | + | The sets of 64 bits are referred to as blocks. | |

| + | [[Image:DES.png|300px|right|The Feistel function (F function) of DES]]<br> | ||

| + | '''DES Modes'''<br> | ||

| + | 1]Electronic Code Book Mode (ECB)<br> | ||

| + | *Encipher each block independently<br> | ||

| + | 2] Cipher Block Chaining Mode (CBC)<br> | ||

| + | *Xor each block with previous ciphertext block<br> | ||

| + | *Requires an initialization vector for the first one<br> | ||

| + | 3] Encrypt-Decrypt-Encrypt Mode (2 keys: k, k')<br> | ||

| + | *c = DESk(DESk^(–1)(DESk(m)))<br> | ||

| + | 4] Encrypt-Encrypt-Encrypt Mode (3 keys: k, k', k'')<br> | ||

| + | *c = DESk(DESk' (DESk''(m)))<br> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | EXAMPLE: The | + | =Public Key Cryptography= |

| - | + | ==Diffie-Hellman== | |

| - | " | + | In 1976, Diffie and Hellman proposed a new type of [[Public_Key_Authentication]] that distinguished between |

| - | + | encipherment and decipherment keys. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | One of the keys would be publicly known; the other would be | |

| + | kept private by its owner. Classical cryptography requires the sender and recipient to share a common key. | ||

| + | Public key cryptography does not. If the encipherment [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Key_(cryptography) key] is public, to send a secret message simply | ||

| + | encipher the message with the recipient's public key. Then send it. The recipient can decipher it using his | ||

| + | private key. | ||

| + | [[Image:deffie.png|350px|right|Deffie example Diagram]]<br> | ||

| + | '''EXAMPLE''': Alice and Bob have chosen p = 53 and g = 17. They choose their private keys to be | ||

| + | -kAlice = 5 and | ||

| + | -kBob = 7. | ||

| + | Their [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_key public keys] are | ||

| + | *KAlice = 175 mod 53 = 40 and | ||

| + | *KBob = 177 mod 53 = 6 | ||

| + | Suppose Bob wishes to send Alice a message. He computes a shared secret key by enciphering Alice's public key using his | ||

| + | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Private_key private key]: | ||

| + | -SBob,Alice = KAlice<br> | ||

| + | *kBob mod p = 407 mod 53 = 38<br> | ||

| + | and enciphers his message using this key (and any desired secret key cryptosystem). When Alice gets the message, she computes the key she shares with Bob as: | ||

| + | -SAlice,Bob = KBob<br> | ||

| + | *kAlice mod p = 65 mod 53 = 38<br> | ||

| + | The mathematical properties of modular exponentiation ensure that for any two users A and B, SA,B = SB,A | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==RSA== | ||

| + | is an [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exponentiation exponentiation cipher]. Choose two large [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prime_numbers prime numbers] p and q, and let n = pq. The totient(n) of n is the number of numbers less than n with no factors in common with n. | ||

| + | The [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Security security] of [http://www.cas.mcmaster.ca/wiki/index.php/Public_Key_Encryption_Algorithms RSA] is based on the difficulty of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integer_factorization integer factorization]: Finding large primes and multiplying them together is easy. However, from the product to find the factors is hard. There is no known efficient general technique to solve this problem. | ||

| + | *'''EXAMPLE''': Let n = 10. The numbers that are less than 10 and are relatively prime to (have no factors in common with) n are 1, 3, 7, and 9. Hence, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Totient totient](10) = 4. Similarly, if n = 21, the numbers that are relatively prime to n are 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, 19, and 20. So totient(21) = 12 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Cryptographic Checksums= | ||

| + | ==HMAC== | ||

| + | Alice wants to send Bob a message of n bits. She wants Bob to be able to verify that the message he | ||

| + | receives is the same one that was sent. So she applies a mathematical function, called a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Checksum checksum] | ||

| + | function, to generate a smaller set of k bits from the original n bits. This smaller set is called the checksum | ||

| + | or message digest. Alice then sends Bob both the message and the checksum. When Bob gets the | ||

| + | message, he recomputes the checksum and compares it with the one Alice sent. If they match, he assumes | ||

| + | that the message has not been changed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''EXAMPLE''': The [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parity_bit parity bit] in the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ASCII ASCII] representation is often used as a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-bit single-bit checksum]. If | ||

| + | odd parity is used, the sum of the 1-bits in the ASCII representation of the character, and the | ||

| + | parity bit, is odd. Assume that Alice sends Bob the letter "A." | ||

| + | In ASCII, the representation of "A" using odd parity is p0111101 in binary, where p represents | ||

| + | the parity bit. Because five bits are set, the parity bit is 0 for odd parity. | ||

| + | When Bob gets the message 00111101, he counts the 1-bits in the message. Because this | ||

| + | number is odd, Bob knows that the message has arrived unchanged. | ||

| + | |||

| + | HMAC is a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generic generic] term for an algorithm that uses a keyless [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_function hash function] and a cryptographic key to | ||

| + | produce a keyed hash function [594]. This mechanism enables Alice to validate that data Bob sent to her is | ||

| + | unchanged in transit. Without the key, anyone could change the data and recompute the message | ||

| + | authentication code, and Alice would be none the wiser. | ||

| + | The need for HMAC arose because keyed hash functions are derived from cryptographic algorithms. Many | ||

| + | countries restrict the import and export of software that implements such algorithms. They do not restrict | ||

| + | software implementing keyless hash functions, because such functions cannot be used to [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conceal conceal information]. Hence, HMAC builds on a keyless hash function using a cryptographic key to create a keyed | ||

| + | hash function. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Summary= | ||

| + | For our purposes, three aspects of cryptography require study. Classical cryptography uses a single key | ||

| + | shared by all involved. Public key cryptography uses two keys, one shared and the other private. Both | ||

| + | types of cryptosystems can provide secrecy and [http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special%3ASearch&search=origin+authentication origin authentication] (although classical cryptography | ||

| + | requires a trusted third party to provide both). Cryptographic hash functions may or may not use a secret | ||

| + | key and provide data authentication. | ||

| + | All cryptosystems are based on substitution (of some quantity for another) and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permutation permutation] (scrambling of | ||

| + | some quantity). Cryptanalysis, the breaking of ciphers, uses statistical approaches (such as the Kasiski | ||

| + | method and differential cryptanalysis) and mathematical approaches (such as attacks on the RSA method). | ||

| + | As techniques of cryptanalysis improve, our understanding of encipherment methods also improves and | ||

| + | ciphers become harder to break. The same holds for cryptographic checksum functions. However, as | ||

| + | computing power increases, key length must also increase. A 56-bit key was deemed secure by many in | ||

| + | 1976; it is clearly not secure now. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Research Issues= | ||

| + | Cryptography is an exciting area of research, and all aspects of it are being studied. New secret key ciphers incorporate techniques for defeating differential and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linear_cryptanalysis linear cryptanalysis]. New public key ciphers use simple instances of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NP-hard NP-hard] problems as their bases, and they cast those instances into the more general framework of the NP-hard problem. Other public key ciphers revisit well-studied, difficult classical problems | ||

| + | (such as factoring) and use them so that mathematically breaking the cipher is equivalent to solving the hard problem. Still others are built on the notion of randomness (in the sense of unpredictability). Cryptanalytic techniques are also improving. From the development of differential cryptanalysis came linear cryptanalysis. The use of NP-hard problems leads to an analysis of the problem underlying the cipher to reduce it to the simpler, solvable case. The use of classical mathematical problems leads to the application of advanced technology to make the specific problem computable; for example, advances in technology | ||

| + | have increased the sizes of numbers that can be factored, which in turn lead to the use of larger primes as the basis for ciphers such as RSA. | ||

| + | Advances in both cryptography and cryptanalysis lead to a notion of "[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Provable_security provable security]." The issue is to prove under what conditions a cipher is unbreakable. Then, if the conditions are met, perfect secrecy is obtained. Similar issues arise with cryptographic [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protocol_(computing) protocols]. This leads to the area of assurance and serves as an excellent test base for many assurance techniques | ||

| + | |||

| + | =References= | ||

| - | + | <div class="references-small"> | |

| - | + | * [[Ross Anderson|Ross J. Anderson]]: <cite>[http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/book.html Security Engineering: A Guide to Building Dependable Distributed Systems]</cite>, ISBN 0-471-38922-6 | |

| - | + | * [[Morrie Gasser]]: [http://cs.unomaha.edu/~stanw/gasserbook.pdf <cite>Building a secure computer system</cite>] ISBN 0-442-23022-2 1988 | |

| - | + | * [[Stephen Haag]], [[Maeve Cummings]], [[Donald McCubbrey]], [[Alain Pinsonneault]], [[Richard Donovan]]: <cite>Management Information Systems for the information age</cite>, ISBN 0-07-091120-7 | |

| + | * [[E. Stewart Lee]]: [http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~mgk25/lee-essays.pdf <cite>Essays about Computer Security</cite>] Cambridge, 1999 | ||

| + | * [[Peter G. Neumann]]: [http://www.csl.sri.com/neumann/chats4.pdf <cite>Principled Assuredly Trustworthy Composable Architectures</cite>] 2004 | ||

| + | * [[Paul A. Karger]], [[Roger R. Schell]]: [http://www.acsac.org/2002/papers/classic-multics.pdf<cite>Thirty Years Later: Lessons from the Multics Security Evaluation</cite>], IBM white paper. | ||

| + | * [[Robert C. Seacord]]: <cite>Secure Coding in C and C++</cite>. Addison Wesley, September, 2005. ISBN 0-321-33572-4 | ||

| + | * [[Clifford Stoll]]: <cite>Cuckoo's Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage</cite>, Pocket Books, ISBN 0-7434-1146-3 | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | =See Also= | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | * [[Conventional_Encryption_Algorithms]] | |

| - | + | * [[Payment_Card_Industry_Data_Security_Standard]] | |

| - | + | * [[Information_Security_References]] | |

| + | * [[Security_and_Storage_Mediums]] | ||

| - | + | =External Links= | |

| + | *[http://security.practitioner.com/introduction/ An Introduction to Information Security] | ||

| + | *[http://www.logicalsecurity.com/resources/resources_articles.html Introduction to Security Governance] | ||

| + | *[http://www.coesecurity.com/services/resources.asp COE Security - Information Security Articles] | ||

| + | *[http://www.davidstclair.co.uk/example-security-templates/example-internet-e-mail-usage-policy-2.html Example Security Policy] | ||

| + | *[http://www.iwar.org.uk/comsec/ IWS - Information Security Chapter] | ||

| + | *[http://www.issa.org/ Information Systems Security Association] | ||

| + | *[http://msdn2.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms998382.aspx patterns & practices Security Engineering Explained] | ||

| + | *[http://www.opensecurityarchitecture.org Open Security Architecture- Controls and patterns to secure IT systems] | ||

| - | [ | + | --[[User:Katmehm|Katmehm]] 23:43, 11 April 2009 (EDT) |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

Current revision as of 03:51, 12 April 2009

Contents |

Introduction

The word cryptography comes from two Greek words meaning "secret writing" and is the art and science of concealing meaning. Cryptanalysis is the breaking of codes. The basic component of cryptography is a

cryptosystem.

Quintuple (E, D, M, K, C):

- M set of plaintexts

- K set of keys

- C set of ciphertexts

- E set of encryption functions

- D set of decryption functions

The goal of cryptography is to keep enciphered information secret. An adversary wishes to break a ciphertext. Standard cryptographic practice is to assume that one knows the algorithm used to encipher the plaintext, but not the specific cryptographic key (in other words, she knows D and E). One may use three types of attacks.

Classical Cryptosystems

Classical cryptosystems (also called single-key or symmetric cryptosystems) are cryptosystems that use the same key for encipherment and decipherment. So the sender, receiver share common key. Keys may be the same, or trivial to derive from one another. The are sometime called symmetric cryptography.

Cæsar cipher

The action of a Caesar cipher is to replace each plaintext letter with one a fixed number of places down the alphabet. This example is with a shift of three, so that a B in the plaintext becomes E in the ciphertext

- EXAMPLE:

The Caesar cipher is the widely known cipher in which letters are shifted. For example, if the key is 3, the letter A becomes D, B becomes E, and so forth, ending with Z becoming C. So the word "HELLO" is enciphered as "KHOOR." Informally, this cipher is a cryptosystem with:

M = { all sequences of Roman letters }

K = { i | i an integer such that 0 ≤ I ≤ 25 }

E = { Ek | k≤ K and for all m M, Ek(m) = (m + k) mod 26 }

Representing each letter by its position in the alphabet (with A in position 0),

"HELLO" is 7 4 11 11 14;

if k = 3, the ciphertext is 10 7 14 14 17, or "KHOOR."

D = { Dk | k K and for all c C, Dk(c) = (26 + c – k) mod 26 } Each Dk simply inverts the corresponding Ek. C = M because E is clearly a set of onto functions.

Vigènere cipher

A longer key might obscure the statistics. The Vigenère cipher chooses a sequence of keys, represented by a string. The key letters are applied to successive plaintext characters, and when the end of the key is reached, the key starts over. The length of the key is called the period of the cipher. Because this requires several different key letters, this type of cipher is called polyalphabetic.

- EXAMPLE: The first line of a limerick is enciphered using the key "BENCH," as follows:

Key B ENCHBENC HBENC HBENCH BENCHBENCH

Plaintext A LIMERICK PACKS LAUGHS ANATOMICAL

Ciphertext B PVOLSMPM WBGXU SBYTJZ BRNVVNMPCS

For many years, the Vigenère cipher was considered unbreakable. Then a Prussian cavalry officer named Kasiski noticed that repetitions occur when characters of the key appear over the same characters in the ciphertext. The number of characters between the repetitions is a multiple of the period.

One Time Pad The one-time pad is a variant of the Vigenère cipher. The technique is the same. The key string is chosen at random, and is at least as long as the message, so it does not repeat.

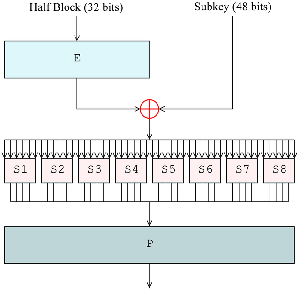

Data Encryption Standard

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) was designed to encipher sensitive but nonclassified data. It is bit-oriented, unlike the other ciphers we have seen. It uses both transposition and substitution and for that reason is sometimes referred to as a product cipher. Its input, output, and key are each 64 bits long. The sets of 64 bits are referred to as blocks.

DES Modes

1]Electronic Code Book Mode (ECB)

- Encipher each block independently

2] Cipher Block Chaining Mode (CBC)

- Xor each block with previous ciphertext block

- Requires an initialization vector for the first one

3] Encrypt-Decrypt-Encrypt Mode (2 keys: k, k')

- c = DESk(DESk^(–1)(DESk(m)))

4] Encrypt-Encrypt-Encrypt Mode (3 keys: k, k', k)

- c = DESk(DESk' (DESk(m)))

Public Key Cryptography

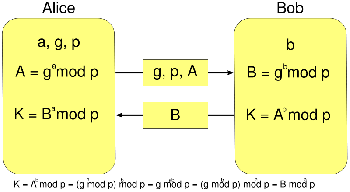

Diffie-Hellman

In 1976, Diffie and Hellman proposed a new type of Public_Key_Authentication that distinguished between encipherment and decipherment keys.

One of the keys would be publicly known; the other would be kept private by its owner. Classical cryptography requires the sender and recipient to share a common key. Public key cryptography does not. If the encipherment key is public, to send a secret message simply encipher the message with the recipient's public key. Then send it. The recipient can decipher it using his private key.

EXAMPLE: Alice and Bob have chosen p = 53 and g = 17. They choose their private keys to be -kAlice = 5 and -kBob = 7. Their public keys are

- KAlice = 175 mod 53 = 40 and

- KBob = 177 mod 53 = 6

Suppose Bob wishes to send Alice a message. He computes a shared secret key by enciphering Alice's public key using his

private key:

-SBob,Alice = KAlice

- kBob mod p = 407 mod 53 = 38

and enciphers his message using this key (and any desired secret key cryptosystem). When Alice gets the message, she computes the key she shares with Bob as:

-SAlice,Bob = KBob

- kAlice mod p = 65 mod 53 = 38

The mathematical properties of modular exponentiation ensure that for any two users A and B, SA,B = SB,A

RSA

is an exponentiation cipher. Choose two large prime numbers p and q, and let n = pq. The totient(n) of n is the number of numbers less than n with no factors in common with n. The security of RSA is based on the difficulty of integer factorization: Finding large primes and multiplying them together is easy. However, from the product to find the factors is hard. There is no known efficient general technique to solve this problem.

- EXAMPLE: Let n = 10. The numbers that are less than 10 and are relatively prime to (have no factors in common with) n are 1, 3, 7, and 9. Hence, totient(10) = 4. Similarly, if n = 21, the numbers that are relatively prime to n are 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, 19, and 20. So totient(21) = 12

Cryptographic Checksums

HMAC

Alice wants to send Bob a message of n bits. She wants Bob to be able to verify that the message he receives is the same one that was sent. So she applies a mathematical function, called a checksum function, to generate a smaller set of k bits from the original n bits. This smaller set is called the checksum or message digest. Alice then sends Bob both the message and the checksum. When Bob gets the message, he recomputes the checksum and compares it with the one Alice sent. If they match, he assumes that the message has not been changed.

- EXAMPLE: The parity bit in the ASCII representation is often used as a single-bit checksum. If

odd parity is used, the sum of the 1-bits in the ASCII representation of the character, and the parity bit, is odd. Assume that Alice sends Bob the letter "A." In ASCII, the representation of "A" using odd parity is p0111101 in binary, where p represents the parity bit. Because five bits are set, the parity bit is 0 for odd parity. When Bob gets the message 00111101, he counts the 1-bits in the message. Because this number is odd, Bob knows that the message has arrived unchanged.

HMAC is a generic term for an algorithm that uses a keyless hash function and a cryptographic key to produce a keyed hash function [594]. This mechanism enables Alice to validate that data Bob sent to her is unchanged in transit. Without the key, anyone could change the data and recompute the message authentication code, and Alice would be none the wiser. The need for HMAC arose because keyed hash functions are derived from cryptographic algorithms. Many countries restrict the import and export of software that implements such algorithms. They do not restrict software implementing keyless hash functions, because such functions cannot be used to conceal information. Hence, HMAC builds on a keyless hash function using a cryptographic key to create a keyed hash function.

Summary

For our purposes, three aspects of cryptography require study. Classical cryptography uses a single key shared by all involved. Public key cryptography uses two keys, one shared and the other private. Both types of cryptosystems can provide secrecy and origin authentication (although classical cryptography requires a trusted third party to provide both). Cryptographic hash functions may or may not use a secret key and provide data authentication. All cryptosystems are based on substitution (of some quantity for another) and permutation (scrambling of some quantity). Cryptanalysis, the breaking of ciphers, uses statistical approaches (such as the Kasiski method and differential cryptanalysis) and mathematical approaches (such as attacks on the RSA method). As techniques of cryptanalysis improve, our understanding of encipherment methods also improves and ciphers become harder to break. The same holds for cryptographic checksum functions. However, as computing power increases, key length must also increase. A 56-bit key was deemed secure by many in 1976; it is clearly not secure now.

Research Issues

Cryptography is an exciting area of research, and all aspects of it are being studied. New secret key ciphers incorporate techniques for defeating differential and linear cryptanalysis. New public key ciphers use simple instances of NP-hard problems as their bases, and they cast those instances into the more general framework of the NP-hard problem. Other public key ciphers revisit well-studied, difficult classical problems (such as factoring) and use them so that mathematically breaking the cipher is equivalent to solving the hard problem. Still others are built on the notion of randomness (in the sense of unpredictability). Cryptanalytic techniques are also improving. From the development of differential cryptanalysis came linear cryptanalysis. The use of NP-hard problems leads to an analysis of the problem underlying the cipher to reduce it to the simpler, solvable case. The use of classical mathematical problems leads to the application of advanced technology to make the specific problem computable; for example, advances in technology have increased the sizes of numbers that can be factored, which in turn lead to the use of larger primes as the basis for ciphers such as RSA. Advances in both cryptography and cryptanalysis lead to a notion of "provable security." The issue is to prove under what conditions a cipher is unbreakable. Then, if the conditions are met, perfect secrecy is obtained. Similar issues arise with cryptographic protocols. This leads to the area of assurance and serves as an excellent test base for many assurance techniques

References

- Ross J. Anderson: Security Engineering: A Guide to Building Dependable Distributed Systems, ISBN 0-471-38922-6

- Morrie Gasser: Building a secure computer system ISBN 0-442-23022-2 1988

- Stephen Haag, Maeve Cummings, Donald McCubbrey, Alain Pinsonneault, Richard Donovan: Management Information Systems for the information age, ISBN 0-07-091120-7

- E. Stewart Lee: Essays about Computer Security Cambridge, 1999

- Peter G. Neumann: Principled Assuredly Trustworthy Composable Architectures 2004

- Paul A. Karger, Roger R. Schell: Thirty Years Later: Lessons from the Multics Security Evaluation, IBM white paper.

- Robert C. Seacord: Secure Coding in C and C++. Addison Wesley, September, 2005. ISBN 0-321-33572-4

- Clifford Stoll: Cuckoo's Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage, Pocket Books, ISBN 0-7434-1146-3

See Also

- Conventional_Encryption_Algorithms

- Payment_Card_Industry_Data_Security_Standard

- Information_Security_References

- Security_and_Storage_Mediums

External Links

- An Introduction to Information Security

- Introduction to Security Governance

- COE Security - Information Security Articles

- Example Security Policy

- IWS - Information Security Chapter

- Information Systems Security Association

- patterns & practices Security Engineering Explained

- Open Security Architecture- Controls and patterns to secure IT systems

--Katmehm 23:43, 11 April 2009 (EDT)